Today is a red letter date in the history of the world, as the Paris Accord comes into effect. Or maybe it isn’t.

The political and activist side of the climate community is portraying the accord as a breakthrough and the beginning of a turnaround in the world’s self-destructive path. Chris Mooney, one of the best reporters on the beat, has a fairly upbeat summary, coauthored with Brady Dennis, at the Washington Post.

But many of us who are scientific and technical professionals have a far less sanguine view of the whole thing. I’ll try to explain why many of us think we remain very far from a sane trajectory. This article is intended for nonspecialists, and it will show a few related graphs showing future carbon emission scenarios.

The intended reader is one who accepts the broad consensus that the long term future of the earth requires limiting the concentration of greenhouse gases far below the level that an unregulated market is likely to achieve.

The Climate Policy Community

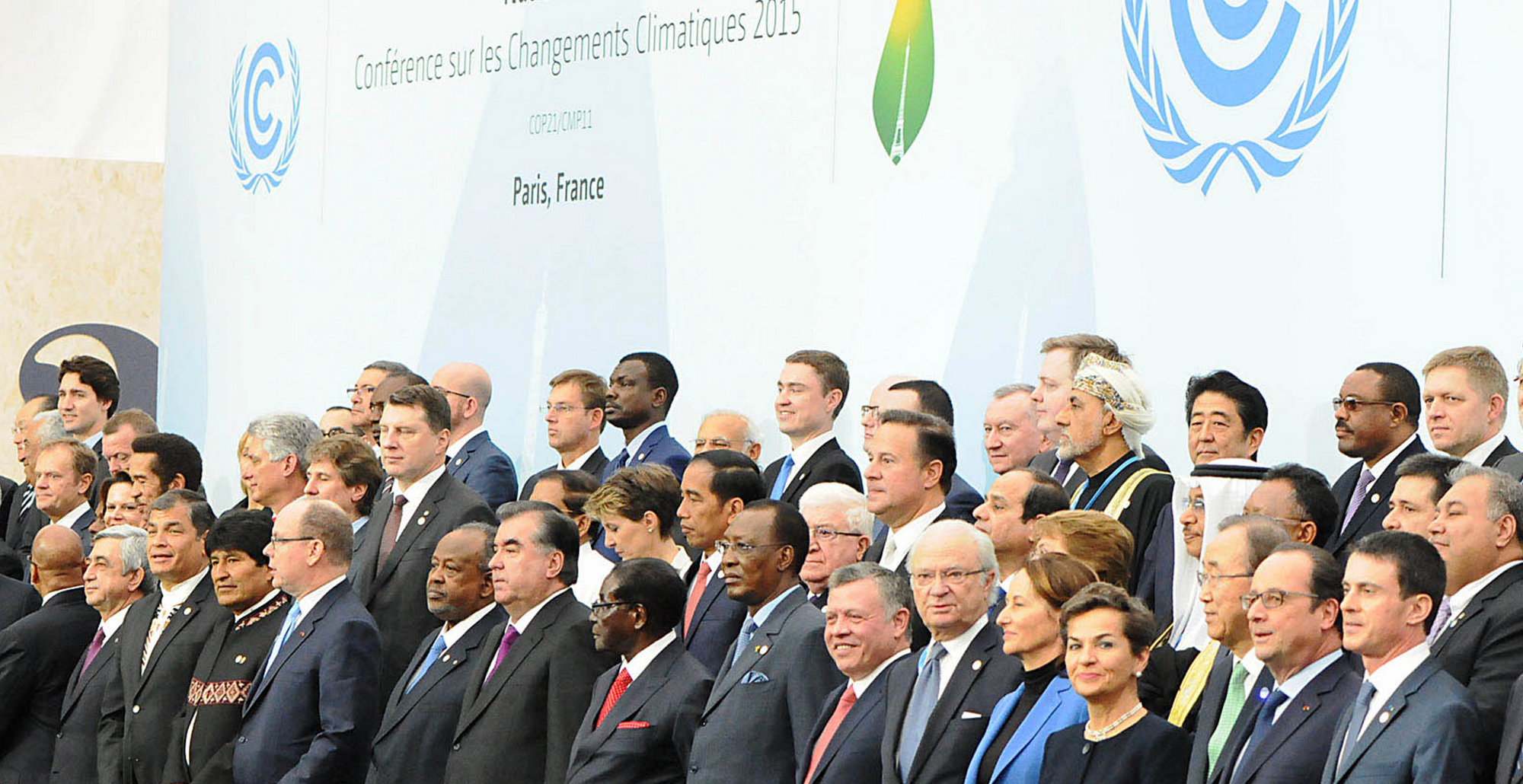

Here’s a little institutional background for those not climate obsessed. The UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) is a world treaty organization which came into force in 1994. (The US, led by George W Bush, is a signatory.) The stated intent of the treaty and the organization is “to prevent “dangerous” anthropogenic (i.e., human-caused) interference of the climate system. To achieve this, annual “Conference of Parties” meetings (COP) have been held, at which meetings global agreement is sought to limit anthropogenic climate change to less than “dangerous” proportions.

The scientific body which informs this effort, IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) predates UNFCCC and is not formally connected to it.

The COP meetings, being worldwide conclaves, are ironically expensive evernts to which thousands of people, representatives of basically all governments and many other organizations, fly from all over the world. The locations naturally have hotels and ariports, and the events themselves can be and are criticized for having a high carbon footprint. Though the critics are generally from the let’s-sneer-about-climate corner, it must be admitted that they have a point, especially insofar as the meetings have not generally been successful.

Attendees insist that the Paris meeting was different, that it should be counted a success. I’m unconvinced.

Carbon Is Forever

A single fact dominates the coming centuries. CO2 does not go away.

The dominant issue in anthropogenic climate change is CO2 accumulating in the atmosphere as a result of human actions. There are other factors in climate change, both natural and artificial. The natural ones are at this point being swamped by artificial ones. Of the artificial ones, most have short time scales (methane) or are somewhat reversible (land surface uses) or are relatively small in impact (CFCs). But CO2 is different from most human impacts on the environment. Its effect is global and persistent.

On historical time scales, CO2 doesn’t go away. While a given carbon atom will shift back and forth between the atmosphere and ocean (and can undergo chemical changes in the ocean) it persists in the environment for a very long time. In particular, carbon from fossil fuels piles up in the atmosphere and ocean.

This means that to solve the problem, we can’t just restrain our emissions’ growth. We have to shrink emissions down to, effectively, zero. Or even less than zero!

While this is certainly a big deal, your first impression might well be that we don’t need a complicated treaty to achieve it. If our target is zero, everybody should just get to zero as quickly as possible. If one country wants wind power, another nuclear power, and another, what, draft horses, so be it. To each their own. Why create a global bureaucracy, when we can all just pull for a good solution?

Libertarian Environmentalism

This approach has academic pedigree.

A Nobel winning economist, Elinor Ostrom, published extensively on the libertarian solutions to the “tragedy of the commons”.

Her approach

… cautioned against single governmental units at global level to solve the collective action problem of coordinating work against . Partly, this is due to their complexity, and partly to the diversity of actors involved. Her proposal was that of a polycentric approach, where key management decisions should be made as close to the scene of events and the actors involved as possible. [Wikipedia]

An example she often referred to was how lobster fishermen in Maine allocated fishing grounds:

You don’t expect big tough fishermen to go around tying bows on baskets, or to get worried if they see a bow they didn’t tie themselves… Maine lobster fishermen use this system when another man sets his traps on their patch. It’s a warning to the poacher that he’s been found out. If he persists, he receives at visit at home. If that doesn’t convince him to mend his ways, he can expect a whole range of other sanctions, up to the destruction of his boat.

This is an example of a self-organising system to manage common pool resources.

Economists, easily impressed by Libertarian arguments, found Ostrom’s arguments “challeng[ing] conventional notions whereby enforcement should be left to impartial outsiders” attractive enough to award her the Nobel Prize (*) in economics.

Can we apply this lobster trap management idea to carbon emissions? After all, seven billion people share a single atmosphere. Can we informally enforce nobody using more than their fair share? The impracticalities are too obvious to enumerate.

The Paris Agreement doesn’t do that directly, but it is a sort of Ostromist agreement writ large. Rather than the individual actors being people, they are countries. Can a community of 197 member nations exert social pressure on one another to comply with a collective goal?

Rejoice, Rejoice, We Have No Choice

I don’t think the past history of climate negotiations offers a reassuring prognosis. There was, nonparticipation of the USA notwithstanding, a Kyoto Protocol signed in 2005. Though there were many intricate details to the agreement, economically advanced (“Annex I”) countries were broadly expected to revert to below 1992 emissions levels by 2012. Non-CO2 emissions, and land use changes were included in a complex formula. Some of the Annex I countries did meet their targets, but many did not. Regarding fossil fuels specifically, most countries emissions got substantially worse. And of course, the nonparticipation in Kyoto by the USA, responsible for a major fraction of the world’s emissions, made the entire agreement of dubious value.

In 2009, an attempt by the world’s nations to enter into a binding agreement on emissions failed in acrimony. At the Copenhagen COP-15, a last minute visit by newly elected President Obama allowed for a sort of face-saving declaration that achieved avoiding the utter collapse of the UNFCCC but little more. It effectively “kicked the can down the road”, delaying picking it up until last year.

The Paris Agreement, signed in 2015 at COP-21, is not a treaty. This was essentially a requirement placed on the negotiations by the USA, which has a Republican dominated Senate, which is notoriously uncooperative with the world on this matter. The US President cannot sign a treaty absent the consent of the Senate, which consent was never going to happen. So a binding treaty including the US is simply not possible.

Instead, we have a global statement of intent, which is nonbinding. It says we’re going to keep global warming below 2 C, which in some convoluted way became the legalistic definition of “dangerous”.

It also has some per-nation not-quite-commitments which don’t add up to an adequate level of decarbonization for even a 3 C target, never mind 2 C.

The hope that this will matter is some equivalent of Ostromist “social pressure”. The parties are to come together in five years and critique each others’ progress. The idea is that each country will strive to do as well as or better than its commitments because of peer group pressure. That is, the idea is that nations will pressure each other as local lobster fishermen do to respect each other’s needs.

Perhaps I’m being a bit more snarky than this entirely deserves. It’s been explained to me that early commitments to the Montreal Protocol eliminating CFCs were inadequate and firmed up over the years. So if we were as competent as our predecessors and the pressures for CO2 emissions were no greater, this might even work too.

But we don’t live in that world. Do you envision “debates” in the US congress being much affected by the desire for approval of America by Maldives or Bangladesh? (In fact, I wonder when the last time was that a vote in the US Congress was affected by testimony or argument from the floor. It must be rare. Bangladesh has no votes.)

The Devil is in the Details

So why the weak sauce?

Why is it so hard to pull together a treaty that everyone (at least everyone not in a country where Rupert Murdoch has hypnotized a swath of the population) could agree to, since the stakes are so high? Tribalist climate denial was not a major force running up to the 2009 Copenhagen COP, and Obama was freshly in office.

Well it turns out that while “zero emissions as soon as possible” is clear enough to the negotiators, “zero by when paid for by whom” is not. This is the international equity problem. Countries that have emitted enormous amounts of CO2 in the past have consequentially amassed great wealth. For them to deny that advantage without compensation strikes the poorer countries as a way to enforce the current distinction between rich and poor forever. They suggest that the people with the money be the ones paying for the new infrastructure.

Then there’s the question of how fast “as soon as possible” really is. Without abundant energy, the world is overpopulated. We can’t just shut off the fossil fuels today and wait for the clean energy to come online someday in the future. The farms must produce. The trucks must roll. The lights must come on. And for some reason, the banks have to stay more or less stable! The existing investment in fossil fuel infrastructure is immense. It’s difficult to imagine how we’d manage things if we had to throw it away overnight. But different economies are in different circumstances. How fast each could commit differs.

Then there are social problems. One could argue that North Americans have emitted our share, that our lifestyles are especially consumptive, and that we could live without private automobiles. But who is going to win an election proposing to every suburban voter that they have to start taking a bus? (Don’t worry, we’ll have train service within two miles of your house in less than two decades!) It would arguably be fair, but it would be a hard sell.

Then there’s the question as to how to count emissions. Global emissions are in principle well-defined. Just check atmospheric and oceanic concentrations, and subtract last year’s value. But how should we count land use changes? How should we count methane emissions? Is the country that pumps the oil responsible for fugitive emissions even if they wouldn’t pump that oil if they didn’t have customers in other countries? What about manufacturing that corporations move to countries where the “as soon as possible” is less soon? (Did Europeans complying with the Kyoto Protocol actually contribute to China’s early 21st century boom by outsourcing heavy manufacturing? Arguably so.)

Trying to get almost 200 sovereign nations to agree on details of this has proven unachievable, even before the rise of widespread climate denial.

One thing we did achieve at Copenhagen was a general ratification of the 2 C target. The previously vague “dangerousness” criterion was replaced, somewhat arbitrarily, with a goal of not allowing near-term global warming to exceed that amount. This agreement was especially ironic, as no treaty was achieved, and no serious progress toward the goal was implemented.

I’ll try below to give you some sense of the urgency that is implied by this goal.

We finally drew a line in the sand.

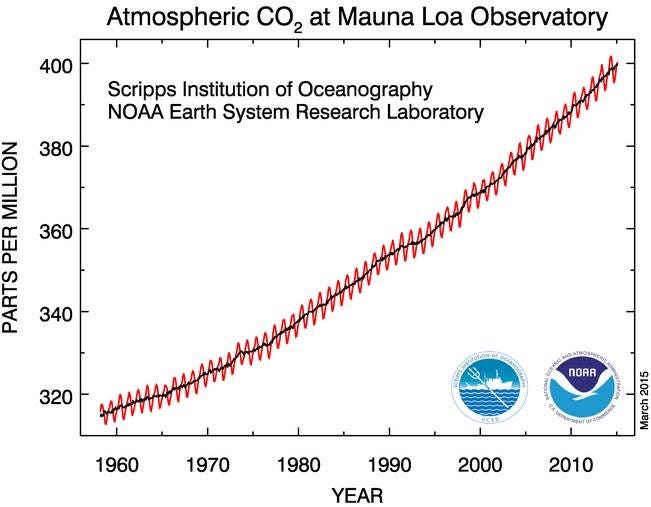

And then we essentially agreed to do nothing about it for six more years. In the intervening years, annual emissions have increased, and the atmospheric CO2 burden has crossed 400 ppmv, about 40% over the preindustrial baseline.

Arguably the objective was falling out of reach at exactly the moment it was agreed to.

The Reality Gap

By 2015, matters were already getting a good deal worse. Climate impacts on the ground were become unambiguous, but dismissal of climate as a real issue had been inculcated in right-leaning commuities around the world, especially in English-speaking countries.

And the 2 C target, a very difficult goal in 2009, was 6 years further out of reach.

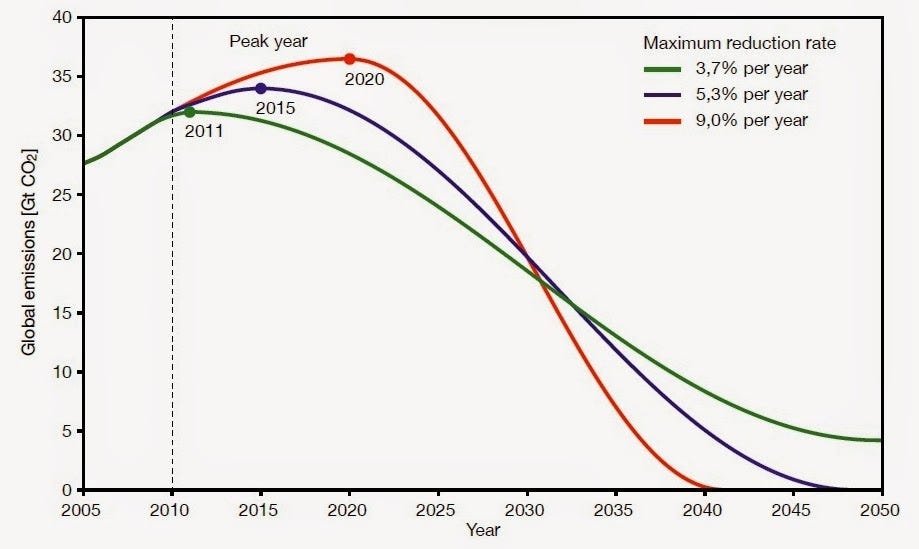

If you are interested in this matter, it’s important to understand how quickly these goals go from feasible to infeasible.

The graph above is the least complicated and easiest to understand of a zoo of future emissions curves. It compares scenarios of global emissions consistent with a likely 2 C peak global temperature excursion. Because CO2 is mostly cumulative, even a short delay means a rapidly increasing effort to get the same result. We have entered the period when the 2 C target is becoming infeasible — emission rate cuts globally in excess of 10%/year.

So just about the time that we agree that 2 C is too much, we missed the boat for 2 C. Should we now fall back to 2.5 C, which there is time to achieve?

Well, in fact, the Paris agreement did quite the opposite. They reaffirmed the increasingly unachievable 2 C goal and added an “aspiration” of limiting global warming to 1.5 C.

Pulling a Rabbit Out of a Hat

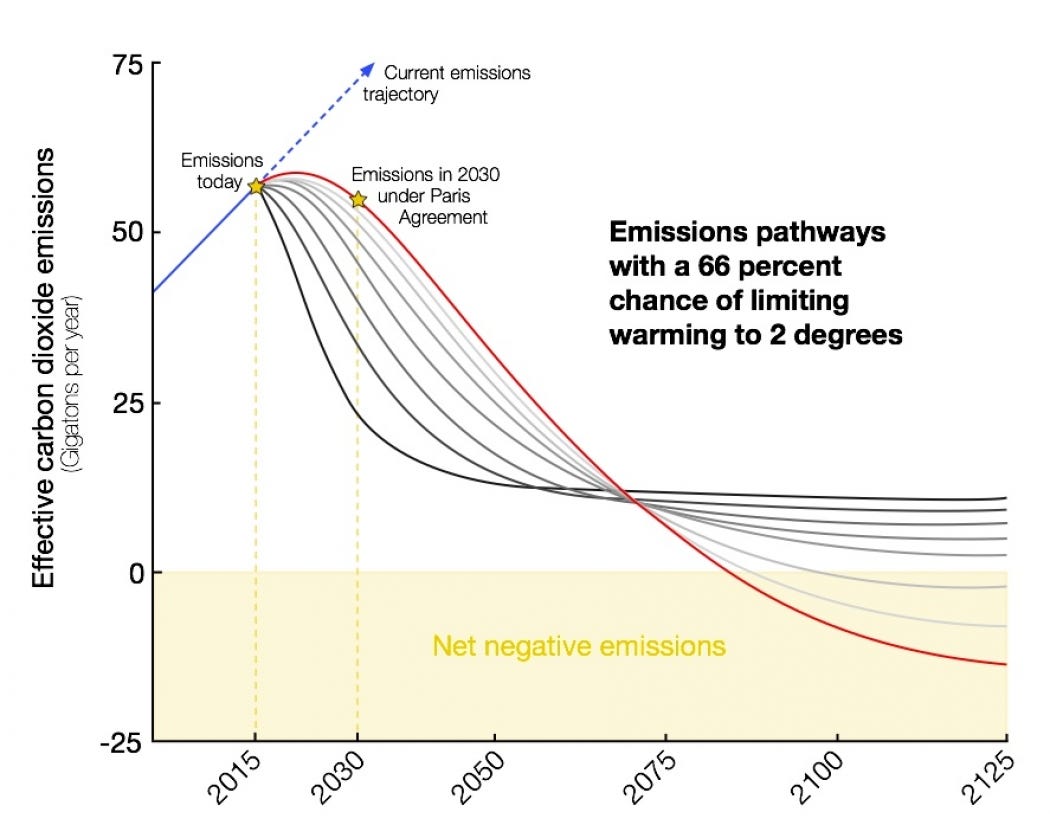

The graph above assumes that emissions can get to zero, but cannot get below zero. This was the ground that all climate discussions was based on in 2009. “Geoengineering”, including large scale capture of carbon from the environment, was considered wild speculation, and not something to base policy on. By 2015, without much in the way of explicit reconsideration, this had been completely reversed. By now, all the realistic scenarios leading to 2 C or less rely on future generations to reverse the damage we are bequeathing them.

This picture is similar to the other one — steeper reductions allow some residual emissions in the long term, but these steeper curves are generally regarded as unrealistic — we don’t really know how to keep a market economy going under the circumstances shown by them.

But there’s a new feature — the intended target trajectory now goes below zero. How are we to do this?

It’s, frankly, unknown.

The leading idea is called BECCS (bio-energy with carbon capture ans sequestration), which means growing crops for energy (on an increasingly land-limited and perhaps food-stressed world), burning them in place (there’s not enough energy surplus to ship the crops long distances) capturing the CO2 in place, piping the CO2 to underground formations, and hoping it stays there.

This may seem implausible to you, and you wouldn’t be alone, but other schemes that have been so far proposed (Cow patties to create soil is a popular one!) turn out to have even bigger holes than this one. This is mostly because, like everything in the energy domain, they are scale limited.

Anyway, suppose it were feasible. Which countries will pay for this enormous operation? What will the motivations be for it? Do we have the right to saddle future generations with a burden like this?

Sorry. It’s too late to ask the ethical question. We’ve made our choice. We have already saddled future generations with this task if we take 2 C as a limit.

It strikes me how different this is from the theoretical way democracy should work. Meeting 2 C or not, committing to carbon negative or not, these are in theory things the public should have put considerable effort into discussing and agreeing upon.

In practice, we have at best backed into a commitment for carbon sequestration. Oliver Geden was the first to point this out, and he got a great deal of resistance for even raising the issue.

More likely, of course, is that large scale capture and sequestration won’t happen, and we need to get by on just limiting emissions. Which in turn means that there is no practical path left to 2 C. Which is what we were saying in 2009, when we warned that the doors to a 2 C outcome were closing.

The Reality Gap

It gets worse, and I hope you’ll bear with me for another emissions scenario graph to make the point. Yes, collectively, we have committed to a path that attains 2 C, albeit with an enormous effort on the part of future generations that we have been unwilling to undertake ourselves. But another part of Paris was the commitments of individual nations. And those don’t add up to anything close to the path we need.

These contributions just don’t add up to what we need. (Well, they don’t subtract up. It’s a peculiar sort of contribution.) To make matters worse, these “contributions” are not commitments. They are more like good intentions. Negotiators at COP-21 were not empowered to make national commitments. But let’s suppose we all manage to live up to our stated intent.

By century’s end on the basis ofthese existing good intentions, we have long since blown past 2 C and are moving toward 4 C, a level which there’s some doubt civilization could survive. We can also surmise that each nation will interpret the fuzzy parts of the calculation to its own benefit, and so emissions will manage to happen that are not counted.

In the end, Paris has left us closer to business as usual than to avoiding climate danger.

But Wait! There’s Less!

Notwithstanding the air of fantasy about these vague gestures in the direction of climate stabilization, the COP wasn’t done. They were just starting to have fun.

Of course, low-lying island nations are already feeling the pain of climate change, and they would like to limit it below 2 C. So they added an “aspirational” goal of limiting warming to 1.5 C. I won’t throw another graph at you. It’s very unlikely we’ll stay below 2 C. 1.5 C is science fiction.

But since we’re announcing things that won’t happen anyway, why not? Let’s also send everybody a pony! I don’t know why free ponies for everybody wasn’t in the agreement too. It’s just as likely as a peak global temperature anomaly limited to 1.5 C.

You Can’t Run A Planet Like a Lobster Fishery

The upshot of this is that there’s little indication that the voluntary, Ostromist vision of bottom-up cooperation and social pressure will save the world. Diversity of approaches is fine, but diversity of goals isn’t.

We need a complex, technical treaty with clear allocation of responsibilities to meet a firm target. And we can’t have one anytime soon.

Perhaps “producing a failure and declaring a success” is so ingrained into the modern world that this bizarre episode makes sense. I know that almost everyone who attended Paris left happy and hopeful. It seems cruel and even malign to pop the balloon.

For now, the Paris Agreement what we’ve got and we should try very hard to make it happen. As you see, I’m pessimistic, but I can’t adequately express to you how fervently I hope to be proven wrong.

Logically it’s time to argue for a hard 2.5 C target (or better, a 500 ppmv concentration target), a real treaty with teeth and lots of paragraphs and subparagraphs about who is responsible for which molecule, and a real global agency which can enforce it.

Emotionally it seems more like it’s time for talking about ponies, and unicorns, and 1.5 C (which is admittedly plenty of climate impact) and to each country their own efforts and different strokes and good luck and kumbaya.

Let’s keep in mind that costs scale nonlinearly. 2 C is not just 33% worse than 1.5 C. Consider that somewhere this side of 80 C, the world simply dies altogether. Impacts appear to increase steeply and nonlinearly with global temperature shifts.

We seem to have attained 1.0 C already, and there’s more warming in the pipeline.

The future will be what it will be, I suppose. It doesn’t look pretty about now.

I just don’t see how wishful thinking helps. I think an ambitious but realistic path to 2.5 C would do more good than a path to 2.o C that depends on fantasy. We still need a global treaty, with realistic goals, detailed national obligations, and teeth.

I noticed your presence in the FB Soil4Climate group. What do you think?

You might remember my biochar (aka terra preta) advocacy in planet3 comments some years back. While that got killed in Copenhagen 2009, it seems soil C sequestration got heard and taken serious in Marrakesh 2016. Methinks BECCS is science fiction (needs astronomic amounts of water) -- But methinks an agricultural revolution could indeed make up for the negative emissions. This is not a task for future generations, but for ours to get rolling.

http://planet3.org/2014/03/05/new-information-on-biochar-and-related-systems/

It appears than carbon-bearing soil has a maximum depth. I have been unable to get a clear sense of how to estimate how much soil the earth can hold. It remains an interest I'd like to pursue. But I don't think a globally important sink can be achieved by agriculture as currently conceived, even by the most forward-looking and earth-centric farmers.

We require some orders of magnitude more soil than originally appeared in nature to make a significant dent in the CO2 excess. And these must be sustained - nature unassisted will not allow it.

Biochar with deep sequestration remains a possibility I have not eliminated. Here I'd worry about recycling of trace minerals. Not much different in principle from BECCS, but I don't know of anyone pursuing it.

I think artificial weathering with olivine is still an open possibility.

As usual, MT, you do a good job here with a lot of stuff.

WRT to the Ostromist approach, I'd hazard not only that it doesn't work, but that it cannot, if one accepts that each state's Govt. is a lobster fisherman.

Thing is, if you govern a state, your first and ultimate duty is to your citizens, not your neighbours'.

Therefore, whichever pathway to whichever posited future you walk, if you are at least nominally interested in the welfare of those to whom you have a primary duty, you have to make tough decisions about sustainability, population, consumption and emissions. But you also have a duty to advocate and act for the best interest of your folks amongst the global community of interested fishermen, however you see it.

The simple bottom line is that allowing an uncontrolled spiralling of BAU works for no state. But likewise, for each fisherman, a choice to restrict one's catch whilst others do not makes little sense - you just end up with hungry children. So what's the supposed 'middle path? 'Voluntary' self regulation - i.e., not catching too many lobsters while that family is getting along fine, and not stopping poorer families from a catching what they need. This doesn't look much like regulation at all.

Underneath all of this, I suspect, is a quandary - it looks like, on the surface, that we can sustain a certain kind of life so long as global population and associated resource use is within certain confines. It also looks like the resource/population metric is already unbalanced and will get even more unbalanced in the next 35 years.

So the various Govts. have a choice - a pathway which reduces current consumption/emissions for one's own folks so that all folks (all 9 billion of them) can have at least a shot at life - or a pathway which secures at least the present state of well-being for one's own, which implies that it is necessary to allow the viability of other's livelihoods, especially in future generations, to slip below the subsistence level, to the 'dead' level.

In other words, the inertia you note is not simply a matter of not knowing what needs to be done, it may be a conscious choice to avoid dealing with the issue, since the moral implications of willed failure are unthinkable. By this means, a state which already has the means to provide for its people can resolve the sustainability problem by letting a few billion people become 'non-viable', i.e., dead. For those states which do not already have the means to provide, there is no option.

The market approach must fail because the only beneficiaries are those who have least to trade and least to use, and any improvement on their welfare must come at the cost of We Others, and our representatives have to protect our interests first.

My suggestion is that developed countries have long-term strategists looking beyond 2050 who have concluded that a certain level of sustainable and comfortable life requires that global population be allowed to 'self-regulate' through simple inaction. Which number constitutes a 'viable' population is a more open question.

My next suggestion is that, moral questions aside, this would not be a winning strategy, because it relies on the assumption that the Disinherited will be passive participants in their own demise.

Finally, there is that moral problem. We, along with our spokespeople, can passively look on from our secure homes as the storm sweeps our poorer neighbours livelihoods and sustenance into the ocean, and make supportive noises. Or we can help them out. Or we can help them become more resilient by sharing some of what we have. Put another way, we can either fight like hell to save as many lives as possible, or we can watch from the sidelines and live with the knowledge that we shared in the responsibility for their loss.

There is a lot more to be said on this, these are just a few current thoughts.

Thanks, Fergus.

Before getting into the details, congratulations, you have just submitted the 10,000th comment to P3!

Thanks for all the hard work. The Oliver Geden link doesn't work, hope you can fix it (I did try search and couldn't find it).

There are a lot of good insights here, and it's a problem that I've been gnawing at: how?

I'll go over to Medium, and recommend others do too. It's where MT, aTTP (Ken), HotWhopper (Miriam), and Greg Laden went after that wholesale denial thing (sorry to be so vague) a while back, also outing their real names.

I took a hard long long, insofar as I was able, at BECCS and came away with a very foul taste. Like all the other magic thinking "solutions" it involves breaking things to fix them, and as mt says, the amount of land it needs to work is staggering. I'm not even sure it works on its merits. It's just complicated enough to fool people into thinking "experts" know. It seems to be a bit like Drax and pellets, in that a good idea (burning useless waste) is turned into a carbon credit machine and purpose grown forests are exported (and the carbon cost of that is stunning) to burn at places like Drax. Ugh!

Will be back, thanks.

To celebrate the possibly 10003rd comment I looked up total land used to produce food in wikipedia, almost 50 000 000km2. Then looked in a German organic gardening book that tells about sequestering 8tCO2/100m2, which is easy according to my small scale biochar experiments. Dividing by 4 and adding up zeroes got me 1000 000 000 000tC, i.e.

1000GtC

that could possibly be sequestered by farming alone. An old estimate of R.Lal says 50-100GtC have been released by agriculture since the industrial revolution.

I agree that ~100 GtC has been released. It seems to me to first order that is how much can be put back.

The extra 900 would be in some sense unnatural soil. How is it to be maintained?

Consider Ornstein et al. "Irrigated Afforestation of the Sahara desert and the Australian outback..." which claims that that is enough trees to sequester about 2 ppm per annum of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Eventually the trees stop growing so some hundreds of years from now the wood is turned into biochar and buried.

The irrigation water is desalinated sea water. This requires energizing. I suggest solar plus some nuclear. The paper, freely available, seems to suggest that US $150 billion per annum suffices.

Of course, we have to stop using fossil fuels.

Got distracted before really finishing...

A major factor missing in my math is the nutrients: N,P,S. There's the major difficulty. I guess we can need less by putting bigger chunks of biochar into the ground. I wouldn't bet my farm on that, but my forest I would bet.

Here is a 2015 talk by my hero Rattan Lal with lots of numbers and giving the grand picture:

https://youtu.be/Uh0TwQyw37A

He doubts a 3GtC/y sequestration rate would be doable. Years back I settled at 1GtC/y armchair estimation.

At 4:30 he shows 486GtC lost by "land use" and 80GtC lost from agricultural land since beginning of agriculture and concludes we have a potential to sequester 500GtC.

"The extra 900 would be in some sense unnatural soil. How is it to be maintained?"

It should be self-maintaining from the start.

(One problem with biochar is perhaps the time it takes for soil microbiome to colonize the deeper char pores, requiring additional nutrients in the process. This depends a lot on the deeper mineral base and longer plant roots (trees, perennials) to extract nutrients from down there. Similarly the breaking up of the char chunks by plant roots and soil animals opens new colonization opportunity requiring additional nutrient input from somewhere. - On the plus side there is usually lots of mineralized P in the soil which is unavailable to aerobic organisms. This could get re-cycled by anaerobic microbes sitting deep in the char pores. (This is my explanation for some of the great successes of biochar/terra preta. Dunno if this theory has meanwhile been examined.))

The maintenance of artificial soils is already a major problem and task of current industrial agriculture:

It destroys soil life: It oxidizes soil organic carbon by plowing. It destroys living nutrient cycles, so the nutrients can run off quickly. And thus it requires huge amounts of fertilizer input to keep the corn growing on fields that would otherwise classify as desert soil. Plus, the wrecked soil biome (plus huge monoculture) makes plants more vulnerable to disease, requiring extra input of pesticides. Quite a vicious circle here, which by itself would call for an agricultural revolution sooner or later.

So there's the difference to BECCS: Soil C sequestration is not straight forward reductionist science and engineering, as rocket scientists, technokrats, and our bean counters would like to have it. (Sorry for snark, but there is a culturally dominant mechanistic mindset that needs to be overcome soon.) Soils are Life, manifesting in diverse species with particular characteristics (minerals plus biome plus above-ground feedbacks). As Rattan Lal puts it beautifully in the video: Soils can go extinct. They are a different kind of construction site to "engineer" and "manage". - But then, we are already treating them brutally recklessly. That can only get better.

If CO2 molecules are beans then I am a bean counter. This question must in the end be answered arithmetically. Even if each soil is a different biome and needs different treatment, in the end, we either collect up a substantial amount of CO2 or not.

Lal is the closest to someone credible who thinks it can be done, but if he can't convince the Vaclav Smil in me, I am not buying it.

Sorry, I was a bit too German. 🙂 Bean counter = accountant, economist.

That's the meaning in English too. But what I am saying is that counting counts.

To Fergus' points, I must sadly agree. Comment 10K captures my personal views exactly.

The trouble is that people speak for themselves and their families. Cities speak for communities and metropoles. Nations speak for their constituent parts. But nobody speaks for the earth. This is despite the fact that everybody has some affinity for the whole earth, whether they've been distracted away from it by xenophobic fearmongering or not.

Creating an institution that limits the power of sovereign nations is not something easily achieved by the nations themselves. They have done it once, not in the feckless United Nations, but in the World Trade Organization, a supernational institution with real powers.

Sometimes I long for a global globalist movement. But I see no reason to imagine that anything the world's population could agree to in a reasonable time frame would be any less shallow and stupid than what they've been voting for locally.

Further, and here I may differ from many of my readers, I neither expect nor desire an abrupt overthrow of the present corporate order. We can't tolerate much in the way of disruption in our current situation.

Consequently perhaps the only remaining hope lies with the corporate super-elite, the Davos crowd, attaching carbon constraints to the WTO. What we need is a better class of oligarch. But the signs in that regard aren't especially promising either, are they?

Thank you, I take it as a compliment that our minds can sometimes think alike.

Ironically (somewhat reflecting your point), it seems likely that a strongly hierarchical (Oligarchic, or similar) system would be better placed to impose order in a globo-corporate, multination world - democracy be damned: if the consequences of the fiasco which these days passes for democracy is anything to go by, 'The People' will choose to look after themselves at the cost of others in line with the smorgasbord of mendacity served up to them as media-reality - and since Nations face the imagined conflict of interest, we need to either bypass them as decision makers and primary causative agents, or demonstrate that the imagined conflict of interest is a fallacy.

For 'The Oligarchs' to be decisive, it needs to be demonstrated that their interest is also served if they 'protect and serve'. I am working on an idea WRT to 'Resistance' which is based on future generations. Will report back when there is more to be said on this.

A really well written piece, Michael.

Odd to hope for an enlightened oligarchy at a time when the U.S. is taken over by the oilygarchy, just like Russia is already, whose only interest (pun intended) is to protect and serve their stranded assets (paradigm: DAPL) in fossil energy.

My hope lies with the poor. More so since Marrakesh perhaps, but I'm not sure the impression I got is for real.

Perhaps we are still thinking too much inside the city box. The city still has the power over the land, like it was from the beginnings of city civilization. The city's power is threatened from two sides now, from within (financial bubble) and from Mother Nature. The latter could be a turning point in history. It seems Africa is getting aware of the importance of soil and sustainable agriculture. The balance of power could reverse: Farmers no longer ruled by city kings. The city now fed by the food-sovereign farmer.

Some hope that the next financial crisis would kill the city (e.g. quite literally, starting with the Miami beachfront housing bubble). But I'm with MT here: "We can't tolerate much in the way of disruption in our current situation." We need to keep most population stuffed in the city and need to keep them happy there. The rest should work the soil and sequester carbon, being poor financially and materially, but owning the production of food and other Life sustaining ecoservices.

Just came across an article by Rattan Lal with a relevant choice quote:

"The goal of the ... proposal is extremely ambitious, but it circumvents the traditional defensive stance of national interest."

http://www.jswconline.org/content/71/1/20A.extract

Free PDF: http://c-agg.org/cm_vault/files/docs/Journal_of_Soil_and_Water_Conservation-2016-Lal-20A-5A.pdf

----

Regarding my 1000GtC estimate in comment above plus my biochar hobbyhorse, here's a key article about abundant natural biochar enriched soil. It makes the estimate of "sequestering 8tCO2/100m2" look conservative. Of course, the problem is the rate...

Rodionov et al (2010), Black carbon in grassland ecosystems of the world, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 24, GB3013

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2009GB003669/full

I see no necessity for poverty of any kind. Every moment that a single person is deprived of basic dignity and comforts by economics is a travesty. Unfortunately, this belief, once widespread, is now considered radical and insupportable.

Thanks. If you want me to be able to keep doing this, it would be helpful to promote the articles I write on Medium.

I may be looking for people to actually buy my books soon as well. Stay tuned.

Will try my best!

Have subscribed to Medium, but found the user experience bad and haven't yet returned. Smells like classical stupid computer engineering. I like planet3.org much more. Actually, I love it.

(Nowadays the KISS principle seems to be worked by simply throwing hypercomplex stupid stuff from the shelf at things. I'm starting to seriously hate modern computering. But my cynism is also developing, being an old Windoze 9x hater. Typo-editing this simple textarea from an Android tablet is devastating enough.)

Medium is much easier to use than WordPress. I need to set up an import/export tool between them, though. It's rather awkward.

Medium's comment facility is peculiar and old-fashioned blogs like this make more sense to me, though. But on the other hand, Medium is set up for network effects and if I am to get anywhere besides talking to a small groups of enthusiasts, I really need some of that.